|

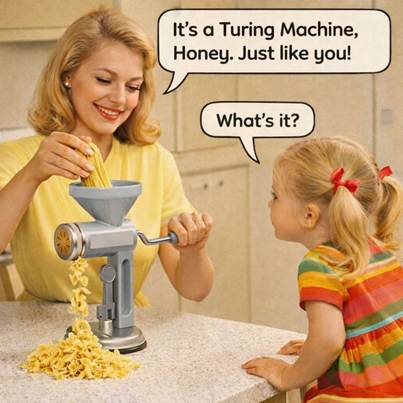

Making ‘farfalle’ the philosophic way

A 1960s-style kitchen image—mother cranking a pasta

machine, child watching farfalle emerge—functions as a precise

diagram of procedural emergence. The pasta machine represents a classical

Turing Machine: a constraint system that transmutes a stream of pliable

input into discrete, repeatable outputs. The farfalle are

not “food” philosophically, but tokens—stable identities produced by

rule-bound transformation. The mother and daughter are not identical to the

machine, but they share its invariant grammar. They are advanced

biological, self-regulating machines that receive unpredictable input, apply

inherited and learned constraints, and emit discrete outputs (actions, words,

decisions). The difference is degree and recursion, not kind. The mother

executes constraints; the child is acquiring them. Crucially, the “raw” input is not metaphysically

random. Every input is the output of a prior machine and functions as

unpredictable only relative to the receiving system. Dough is raw for the

pasta machine; farfalle will be raw input for chewing, digestion, and further

processes. At deeper levels, even the first emergents

are already quantised and discrete. Randomness is operational, not absolute. No meaning is implied. Constraint systems do not

interpret; they compress degrees of freedom into tokens. Any felt

meaning is a local, contingent side-effect within certain machines navigating

open, unpredictable contexts—not a property of the process itself. The mother’s line—“It’s a

Turing Machine, honey. Just like you!”—is therefore procedurally exact. The

image reveals a general law: all stable identities are outputs of

constraint-driven machines, and every output becomes someone else’s input. Making ‘farfalle’ the philosophic way, adv. |